Don't use Wingdings

Here’s a fun way to pass the time. If you like discussing the intimate details of character encodings, that is. Or reverse engineering various Microsoft products to see how broken they are.

If you don’t think this is fun, then please just take my advice and move on. Don’t use the Wingdings for anything. If you’re a developer, embrace Unicode. That’s it. Nerds, read on…

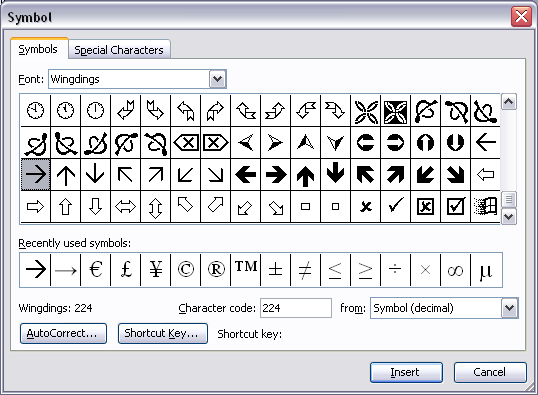

Open up a new document in Microsoft Word 2003 on Windows XP. Choose Symbol from the Insert menu. Set the font to Wingdings and insert the Right Arrow character:

So you think you’ve just inserted a right arrow into the document eh? OK well try saving the document as HTML and opening it in Mozilla. What do you see?

That’s right, there’s an à where your arrow should be, in both the title and body of the document. The same thing can happen if you copy and paste into FrontPage, and then use “clear formatting”. Or into Outlook.

In fact it’s far worse in Outlook, because when you’ve selected “Plain Text” as the format for the email, the right arrow still appears as a right arrow, but when it’s sent it changes to an à. I find it just incredible that anyone would design an email program this way.

Given this breakage, it seems the safest thing to do is not use Wingdings at all, at least on Windows (see below for MacOS X comparison). Instead use a Unicode font like Arial - it’s got all the symbols you’ll ever need. And if it doesn’t have the right symbol for you, you probably should be embedding a graphic.

So what’s really going on here? Look more closely at the insert symbol dialog box above. See the character code is listed as 224? Well, let’s look at Unicode character 224: à. Hmm, looks mighty familiar!

Basically Wingdings is it’s own character set. That is, it contains it’s own mapping of character codes to characters. So where Unicode uses 224 to represent an à, Wingdings uses it to represent a right arrow. Where Unicode, US-ASCII and most other character sets use the value 65 to represent a capital A, Wingdings uses it to represent a hand with two fingers up in a V for Victory sign (not unlike ✌, the unicode VICTORY HAND). Note that in each case the characters are semantically different. Compare two fonts like Arial and Times New Roman, and you’ll find that the appearance might be different for the same character code, it’s still the same character.

So it’s OK to use multiple character sets in Word, as long as you trust it to keep track of which parts of your document use which character encodings. I hate to think of the complexity behind the scenes.

The problem comes when you go to other domains that don’t allow mutliple character encodings. Like the web (and I’m including HTML and XML here). These formats have no need to support multiple character encodings, because we have Unicode. Basically as soon as you publish your Word document with all it’s funky character encodings as HTML, it becomes an incomprehensible mess (or in my case, more of an incomprehensible mess) because it screws up the transcoding of symbol characters to Unicode.

You might be wondering whether or not Word is even capable of translating the different character encodings, that it obviously uses under the covers, into Unicode. Well if you save the document as XML, look how it gets encoded:

<w :sym w:font="Wingdings" w:char="F0E0"/>

OMG, what were they thinking? Check out the documentation for the w:sym element. It’s a single character (presumably unicode, but that’s a spec problem) represented as … an XML element. OK so maybe you don’t buy all this XML philosophy about text versus markup, but on a purely practical level, if every XML parser in the world can understand this character encoded as an entity (ie ), then that should be the way to go, right?

As it stands, every application that wants to reliably parse the text from a WordML document has to special-case the w:sym element. OK it’s not a difficult fix, probably three lines worth of XSLT, but I mean really.

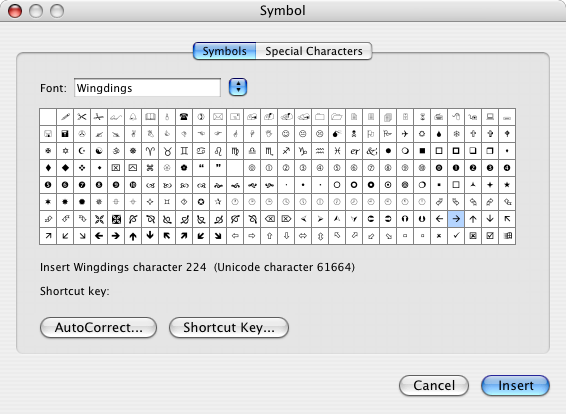

Anyway what this does show is that Word 2003 can do the Wingdings to Unicode mapping, albeit only for certain output formats (ie XML and not HTML). So what happens on the Mac? Have a look at the insert symbol dialog on Word 2004 for MacOS X:

Well lookee here. It does a translation of the inserted character into unicode at the time you insert it! Character code 224 becomes Unicode character 61664, which looks like this: . If you’re like me you probably don’t have a glyph for this character and your browser is probably displaying a question mark. That’s because this character is in the private use area of the Unicode codepoint range, where they don’t define any characters.

When you save this document as HTML and view it in a browser, the right arrow appears in the title bar as →. That’s Unicode character 8594 (0x2192), otherwise known as RIGHTWARDS ARROW. Hooray, a successful transcoding from Wingdings to Unicode! The same thing happens if you choose to save the document as Unicode text.

Unfortunately in the body of the HTML document it all goes to pieces. Word writes out a à character, with the Wingdings font applied via an inline style. Oh dear.

[Incidentally Camino and Firefox on MacOS both get this totally wrong and display something like a ⇗ instead. Safari gets it right though.]

So Word 2004 on the Mac is doing a slightly better job than Word 2003 on Windows. It seems to be converting the Wingding symbols into unicode when you insert them. Unfortunately, instead of mapping the characters into their correct Unicode code points like it should be doing, it just uses the private use area. Probably a hack - it wouldn’t surprise me if Unicode is actually a requirement for application interoperability on MacOS.

So far I’ve picked on Wingdings, but really the message is not to use any non-standard character sets. This includes the other dingbat fonts like Symbol, Zapf Dingbats, Webdings, etc.

I have no opinion on the Wingdings typeface as a collection of glyphs. However the reason you shouldn’t use it is because it uses a different character encoding from, well, everything else. I’m sure the reasons are historical, and at some point Wingdings will be re-encoded to make it a Unicode font. Or maybe Word will get smarter about transcoding it into Unicode. Until that time steer clear of it and all like it.

As stated above, use a Unicode font instead. On the Mac, get used to the “Special Characters…” pallette. On Windows, the Character Map application is your friend; turn on “Advanced View” and look for Unicode fonts. All the characters are in there, waiting for you to use them.

(Disclaimer to all the above: I am not a Unicode or character encoding or even a typography guru. Consult your doctor if pain persists.)

10 Comments