Star Wars in ASCII ... and IPv6

I’m rather shamed to admit that the following was the final straw that pushed me into deploying IPv6 on my home network.

This is from ASCII Star Wars, which you can see for yourself by telneting to towel.blinkenlights.nl. And after you’ve basked in ASCII goodness, read on for the IPv6 experience.

So by now everyone knows that IP addresses of the future have 128 bits, right? One for each atom in the universe or some such hyberbollocks. So I won’t go into the basics of IPv6, just take it as read.

What I will say is that my ISP rather unsurprisingly does not offer IPv6 connectivity, so like most early IPv6 adopters I need to decide on which interoperability mode to use. There are a surprisingly large number of options (but not one for each atom in the universe, thankfully). I won’t even being to summarise them, but I will try to illustrate the IPv4/IPv6 interoperation method that I chose for my home network: 6to4. Mainly because, hey, I think it’s cool.

6to4 is a rather ingenious method of addressing and tunnelling IPv6 packets in IPv4 packets. The way it works is that there is a 6to4 gateway somewhere on the internet. If you want to connect your IPv6 network with the rest of the IPv6 internet, you tunnel through the IPv4 network to the 6to4 gateway, and out again. The really clever part is that you don’t need to set up the tunnel beforehand with a 6to4 provider (which is what is needed to use some of the other tunnel protocols).

Obviously you want the 6to4 gateway to be as close as possible. To avoid the hassle of finding out exactly where this gateway might be (and re-routing if it goes down), the Brains of the Internet decided on an “anycast” address for this gateway: 192.88.99.1. The idea is that you use this address as a 6to4 gateway, and your upstream network provider will route it to the best 6to4 gateway for your location in the network. Clever, eh?

Well, sorta. Unfortunately it depends on your upstream provider caring enough to direct the 6to4 anycast address somewhere sensible. Fortunately all it takes is a simple traceroute to find this out. And if the nearest 192.88.99.1 address to you turns out to be on the other side of the planet, well you don’t have to use that address. I ended up using the AARNET relay router, one of many posted to the Nick’s list of public 6to4 relay routers.

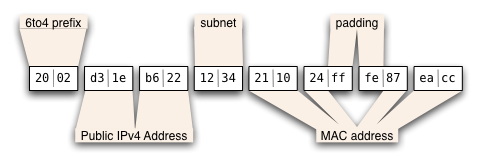

OK so how do the IPv6 packets get back to you? There’s a special IPv6 prefix (i.e. the network part of your IPv6 address) which is 16 bits long and looks like this: 2002::/16. This prefix has been set aside for all 6to4 tunnels. The way you construct your /48 prefix is by … appending your public IPv4 address. So if your public IP address is 1.1.1.1, then you already have an IPv6 prefix of 2002:0101:0101::/48. This means that the 6to4 router knows exactly how to get packets back to you without maintaining any state about your or your connection. When it has an IPv6 packet to send to you, it just wraps an IPv4 packet and addresses it using the address embedded in the prefix. I think this is clever.

So I set up 6to4 on my OpenWRT router, using the instructions on the wiki. ping6 www.kame.net no problems.

Now IPv6 has this thing called stateless auto-configuration. The way it works is that an IPv6 router (such as my trusty OpenWRT box) advertises itself using multicast on the local network. It says “hey I’m an IPv6 router, and if you want an IPv6 address, assign yourself one in this prefix: xxxxx”.

The IPv6 clients listen to this and think “hmm, IPv6 eh? sounds great”. They then think “hey! why do we have such a cheesy anthropomorphisation?!”. Which is a good question.

Anyway the advertised prefix can include a subnet so that the hosts see a /64 instead of the entire /48. This might be handy if I decide to use a different subnet for the wired network than the wireless network.

The clever part about IPv6 stateless auto-configuration is the way that the IPv6 hosts assign their addresses within the advertised prefix. Basically they use their MAC address (with a minor bit fiddle). Yep, IPv6 has enough addresses to allow 48-bit MAC addresses to be used for host identifiers, with padding.

The result is a monster address that you’d never want to type, but which makes sense when you look at all the parts. (This is my first ever drawing in OmniGraffle. Be gentle!)

All this is enough to make the turtle dance, provided that you use some tweaks to get browsers working with IPv6. Other than the browser configuration, no extra tweaking was needed to get IPv6 working with MacOS X. FreeBSD requried a simple sysctl to listen to the router advertisements. Windows XP, well, I didn’t try.

So if you’ve read this far hoping to find out how much better ASCII Star Wars looks over IPv6 …. well let’s just say you’re in for a surprise. A surprise that I am not about to give away, sorry. Yep, I’m a a bastard that way.

0 Comments